Africa isn’t just laying fibre; it’s building ports for the AI economy. In the 19th century, maritime harbours decided who controlled trade.

In the 21st century, the new choke points are data centres—the places where subsea cables make landfall, networks interconnect, and compute meets demand.

As investment accelerates from Lagos to Nairobi to Johannesburg, Africa’s data centres are becoming strategic assets that will shape who captures value from AI, fintech, media, and the broader digital economy.

According to the Africa Data Centres Association (ADCA), the continent has about 307 megawatts (MW) of live capacity—less than 2% of the global total. That’s a thin foundation for 1.4 billion people entering a data-intensive era.

This cornerstone guide explains where the build-out is happening, why these facilities function like digital ports, and what it will take for Africa to anchor more of the AI value chain at home.

Why data centres are the new ports

A data centre is a highly reliable building that houses servers, storage, and networking equipment. It provides power, cooling, and security so applications never go down.

In the AI era, it also needs to support GPU (graphics processing unit) clusters for training and inference (running models), as well as low-latency links to users and partners.

Ports once determined trade routes and tariffs. Africa’s data centres now determine latency, data sovereignty (who controls and can regulate data), the cost of cloud, and the carbon footprint of digital growth.

Where these facilities sit—and who owns them—will influence everything from streaming quality to payment resilience to where African startups can affordably deploy AI.

Visa’s new processing site in Johannesburg, for example, keeps more payment activity on the continent and reduces dependence on overseas infrastructure. According to Reuters (2025), it’s the company’s first data centre in Africa and part of a multiyear investment.

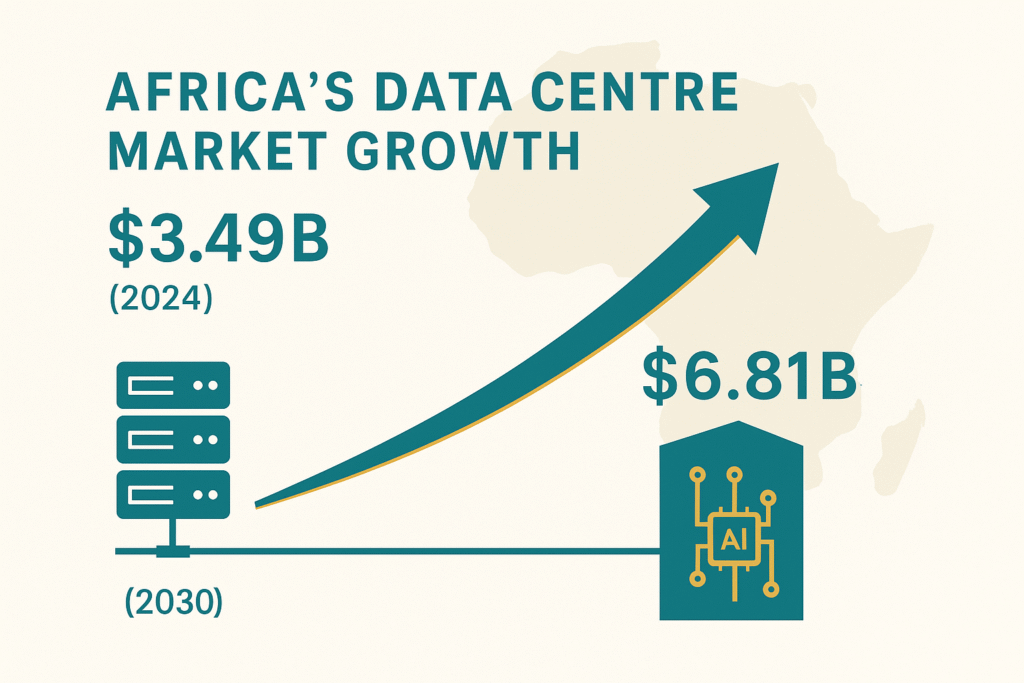

The market at a glance

- Installed capacity: ~307 MW live across Africa, still a small share of the world’s total.

- Growth need: Analysts and developers expect a multi-fold increase by 2030, with sustained demand from cloud, video, gaming, and AI. (Multiple industry reports and operator roadmaps point to this trajectory.)

- Value pool: Market researchers estimate the Middle East & Africa data centre market at $8.63 billion in 2024, projecting a value of approximately $19.9 billion by 2030. While that regional figure includes the Middle East, it underscores the scale of momentum that African hubs can leverage.

Where is the action?

- South Africa leads in installed capacity and interconnection density. Teraco (Digital Realty) recently completed JB5 in Johannesburg, increasing the Isando campus’s capacity to ~70 MW.

- Nigeria is emerging as West Africa’s hub, with Rack Centre’s new 12 MW LGS2 site in Lagos and hyperscale plans from Airtel’s Nxtra.

- Kenya is scaling fast on a greener grid, from iXAfrica’s Nairobi campus to Nxtra’s new build at Tatu City.

- Morocco is planning a 500 MW renewable-powered campus, positioning itself as a North African compute anchor.

How Africa Plans to Bridge the Capacity Gap

Africa’s installed capacity of 307 MW is a fraction of global supply, but the pipeline is swelling. By 2030, experts anticipate the continent will add hundreds of megawatts through active projects, public–private partnerships, and development finance.

What’s driving expansion:

- Private operators scaling campuses: Teraco’s JB5 adds ~70 MW in Johannesburg, while Rack Centre and Airtel Nxtra are building facilities in Nigeria with combined capacity beyond 50 MW.

- Regional builds: Raxio, backed by IFC’s $100 million investment, is expanding in Ethiopia, the Ivory Coast, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- Hyperscaler investments: Google Cloud opened its Johannesburg region in 2024; Microsoft and AWS are expected to follow with regional expansions.

- Renewable mega-sites: Morocco’s planned 500 MW green-powered campus is designed to meet the demand for hyperscale AI.

- Policy incentives: Tax breaks in Nigeria’s free trade zones, land allocations in Kenya’s Tatu City, and renewable PPAs in South Africa are creating more attractive economics.

These steps show that the continent’s gap isn’t a vacuum—it’s an opportunity that multiple actors are rushing to fill.

Digital ports need sea lanes: Equiano and 2Africa.

Ports are only as valuable as the trade routes they connect. In the digital economy, those routes are subsea cables. Two systems are changing Africa’s map:

- Google’s Equiano (Atlantic route) has landed in Togo, Nigeria, Namibia, South Africa, and others, with economic studies forecasting faster speeds and lower prices as capacity is increased. Google highlighted expected speed and price improvements; an independent assessment by Africa Practice and Genesis Analytics modelled a 21% decline in retail internet prices and speed gains in Nigeria by 2025.

- 2Africa (Meta-backed): a 45,000 km system connecting 33 countries and 46 landing stations, designed to triple Africa’s subsea capacity on key routes. Segments have already gone live in Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa.

Why it matters: Cables deliver international capacity; Africa’s data centres localise and monetise that bandwidth. Traffic “docks” at neutral facilities where carriers peer, clouds interconnect, and content caches. That’s where latency drops and value sticks.

Five data centre projects shaping the map (now)

1) Teraco JB5, Johannesburg (South Africa)

Teraco, owned by Digital Realty, completed its JB5 facility in 2025, bringing its Isando campus to ~70 MW. The company also signed renewable power purchase agreements to improve its energy mix.

For AI builders, South Africa’s scale, combined with its interconnection density, is the closest thing Africa has to a “Tier-1” digital port today.

Why it’s important:

- Brings hyperscale-ready capacity near the most significant enterprise and cloud market in Africa.

- Interconnect-rich campuses compress latency between clouds, CDNs, banks, and telcos—critical for AI inference and fintech.

2) Rack Centre LGS2, Lagos (Nigeria)

Rack Centre switched on its 12 MW “AI-ready” LGS2 build at Oregun in March 2025. The facility is carrier- and cloud-neutral, featuring multiple data halls and an energy plan that incorporates gas, diesel, and planned solar sources.

Why it’s important:

- Positions Lagos as a West African hub with local resilience and lower round-trip times to users.

- “AI-ready” power and cooling profiles support higher-density racks.

3) iXAfrica Nairobi Campus (Kenya)

iXAfrica launched East Africa’s first large-scale hyperscale, carrier-neutral, AI-ready data centre with an initial 4.5 MW phase and a roadmap beyond 20 MW. In September 2025, the company secured RMB financing to scale to ~22.5 MW at completion.

Why it’s important:

- Sits on a grid with substantial geothermal generation, improving the path to greener compute.

- Provides regional startups and public sector agencies with a local platform for running low-latency AI workloads.

4) Equinix JN1, Johannesburg (South Africa)

Global interconnection leader Equinix opened JN1 in Johannesburg, following an announcement of a US$160 million investment plan. The site acts as an IBX hub for colocation and fabric interconnects, enhancing multi-cloud routing for enterprises.

Why it’s important:

- Brings Equinix’s Fabric ecosystem to Africa, making it easier to stitch together multi-cloud and network services.

- Strengthens South Africa’s position as an on-ramp to global platforms.

5) Visa Data Centre, Johannesburg (South Africa)

Visa opened its first African data centre in 2025, expanding the company’s VisaNet processing network locally. For payments, computation close to customers is about more than speed; it’s about compliance, resilience, and sovereignty.

Why it’s important:

- Reduces dependence on out-of-region processing for African transactions.

- Signals that mission-critical financial workloads are now viable on the continent.

Uganda has also recently announced plans to build Africa’s first AI Factory powered by NVIDIA.

Huge builds coming into view.

- Morocco’s 500 MW renewable-powered facility: The government announced plans for a half-gigawatt data centre powered by renewables—one of the most ambitious projects in Africa to date. Location decisions align with the country’s energy strategy and data-sovereignty goals.

- Airtel Africa’s Nxtra program: Ground broken on a 38 MW site in Lagos and a 44 MW Tatu City (Nairobi) facility designed for GPU-ready racks, staged in phases through 2026–2027.

- Africa Data Centres (ADC) + DPA solar PPA: ADC and DPA (a power producer) are building a 12 MW solar farm to serve South African data centres—part of a broader shift toward dedicated renewables for uptime and emissions control.

Together, these announcements show how Africa’s data centres are scaling capacity, integrating green power, and preparing for high-density AI compute.

Regional Dynamics: Who Plays What Role?

South Africa: Scale and interconnection.

- Deep enterprise market and public clouds, with a high density of neutral facilities.

- Growing renewable PPAs (e.g., wind/solar) as operators hedge against grid instability and decarbonise.

Nigeria: West African gateway.

- New builds from Rack Centre and Airtel Nxtra strengthen Lagos as a digital port for fintech and media.

- Equiano’s earlier landings support capacity; local hosting trims latency to Nigerian users.

Kenya: Green-tilted compute and regional finance.

- iXAfrica’s expansion and Nxtra plans align with a cleaner grid mix and a robust developer ecosystem.

- Activation of 2Africa segments connecting Kenya with Tanzania and South Africa improves cross-coast latency.

Morocco & North Africa: Renewable-led ambition.

- The 500 MW proposal aims to align compute with abundant wind/solar resources, positioning Morocco as a North African hub.

Power, cooling, and sustainability: the hard constraints

Data centres are power-hungry. In markets with grid shortfalls and load-shedding, uptime often depends on diesel or gas generation—expensive and carbon-intensive. The shift is underway:

- Solar and wind PPAs: Operators are signing long-term renewable energy deals to stabilise costs and reduce emissions. Teraco’s wind PPA is one example; ADC’s 12 MW solar farm is another.

- Efficient design: Best-in-class facilities achieve a PUE (power usage effectiveness) of 1.2–1.3 and utilise advanced cooling, containment, and DCIM monitoring. (Vendors and operators across the region publish these design targets; see iXAfrica’s published PUE 1.25 campus benchmark.)

- Water stewardship: In water-stressed regions, non-evaporative cooling and heat-reclaim strategies matter. Expect scrutiny and incentives to drive the adoption of dry cooling and circular water loops where feasible.

Bottom line: Power sourcing and efficiency will decide where Africa’s data centres can host AI at scale. The economics of GPUs, power, and cooling are welded together.

Sovereignty, compliance, and trust

As workloads localise, policy decides how far they move. Data protection and residency rules—from Nigeria and Kenya to pan-regional frameworks—are shaping where sensitive workloads land. For payments, the Visa build shows that major platforms view local processing as a competitive and regulatory advantage. Reuters

Operator ownership also matters. Neutral colocation can attract a mix of carriers and clouds; hyperscaler-owned regions (like Google Cloud Johannesburg) anchor ecosystems and skills. Google launched the area in January 2024, giving enterprises a local on-ramp to analytics and AI services. Google Cloud

Data Sovereignty – The Regulatory Compass

Infrastructure growth is only half the story. The other half is who controls the data that lives in these facilities. As Africa’s data centres expand, regulation is shifting from soft guidelines to burdensome mandates.

- National laws already in force:

- Nigeria’s Data Protection Act (2023) requires stricter oversight of cross-border data flows.

- Kenya’s Data Protection Act (2021) mandates registration for data processors and controllers.

- South Africa’s POPIA (Protection of Personal Information Act) enforces compliance on local handling of sensitive data.

- Regional harmonisation efforts: The African Union’s Digital Transformation Strategy (2020–2030) calls for unified frameworks, echoing the EU’s GDPR model.

- Localisation trends: Governments are increasingly requiring financial, healthcare, and government workloads to be processed domestically. Visa’s Johannesburg data centre is a direct response to these sovereignty requirements.

Looking forward, expect sovereign cloud zones within African data centres—isolated environments where sensitive data never leaves the country. This shift could reshape who builds facilities and how they are financed.

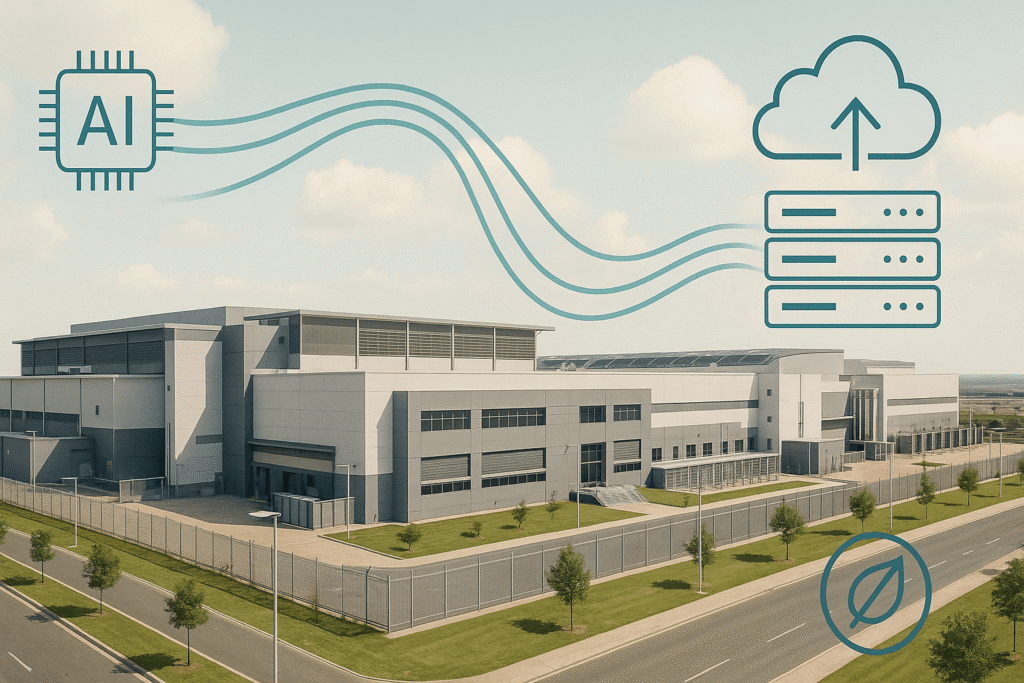

AI-ready means different design choices.

AI isn’t business as usual. Africa’s data centres that plan for AI do a few things differently:

- High-density racks (20–40 kW or more each) for GPUs/accelerators.

- Liquid-ready cooling paths (rear-door heat exchangers or direct-to-chip), even if air remains dominant today.

- Fat pipes for east-west traffic and storage: more spine-leaf, 100–400 GbE, and dark fibre paths.

- Grid + on-site generation hybrids: renewables, batteries, and gas/diesel backup with fuel logistics.

- Security & compliance tuned for regulated AI (health, payments, public sector).

Early signals are visible. Rack Centre touts AI-ready density, iXAfrica publishes per-rack power targets, and Nxtra markets GPU-ready racks in both Nigeria and Kenya.

What top-tier “digital ports” look like (checklist)

To separate marketing from reality, look for:

- Carrier- and cloud-neutral design with multiple fibre routes and rich peering capabilities.

- Tier III/IV certifications or equivalent design objectives, plus strong incident metrics.

- Published PUE targets and a roadmap for renewable PPAs.

- AI-readiness: liquid-cooling pathways, high-density power per rack, and floor loading for GPU clusters.

- A campus scale that allows modules to be added without downtime.

- Regulatory posture: apparent compliance for financial services, health, and government workloads.

Local Economies and Skills – Beyond the Buildings

The growth of Africa’s data centres isn’t only about megawatts and cables; it’s also about jobs, skills, and ecosystems.

Construction phase: Large campuses employ 500–1,000 workers during build-out, including civil engineers, electricians, plumbers, and security teams. These are short-term but inject cash into local economies.

Operational phase: Once live, facilities require 50–150 specialised staff per site. These are high-value roles, including electrical engineers, HVAC specialists, network engineers, and site reliability professionals.

Multiplier effects:

- Cloud providers often pair new regions with training programs. Google’s Johannesburg cloud launch included scholarships for African developers.

- Startups and SMEs benefit from reduced latency and lower cloud costs, which stimulates the fintech, health-tech, and creative industries.

- Cities benefit indirectly: A stable data infrastructure attracts multinational companies, which in turn expand office parks and support local services.

Over time, this ecosystem effect can rival the impact of a manufacturing plant—except the exports are services, innovation, and AI applications rather than physical goods.

Case-by-case: how the “port” metaphor plays out

- Johannesburg acts like Durban once did for shipping: the first stop for oversized cargo. With Teraco, Equinix, Google Cloud, and Visa, the metro concentrates subsea capacity, cloud on-ramps, and payment processing.

- Lagos is the West African quay: dense telco activity, Equiano landings, and data-hungry fintechs. Rack Centre and Nxtra add bays and cranes—more power, more interconnects, more compute.

- Nairobi is a green hub for computing: a geothermal-heavy grid, a strong developer base, and regional financial links. iXAfrica and Nxtra are expanding berths for AI-grade cargo. 2Africa activation between Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa tightens coastal links.

- Morocco could be a wind-and-sun-powered deep-water port for computing if the 500 MW plan advances—pairing large capacity with large renewables.

Risks that could slow the build-out

- Power shortages and grid volatility: Outages add cost and risk. This is why operators are racing to sign dedicated renewable PPAs and build behind-the-meter capacity.

- Capex and financing: Tier III/IV builds and AI retrofits are capital-intensive. IFC’s $100 million investment in Raxio demonstrates the role of development finance in attracting private capital.

- Regulatory fragmentation: Inconsistent data rules complicate multi-country deployments.

- Skills gap: Running modern data centres and AI clusters takes specialised operations talent—electrical, mechanical, network, and SRE.

- Water scarcity & community impact: Expect stricter rules around water-based cooling and ESG disclosures as campuses grow.

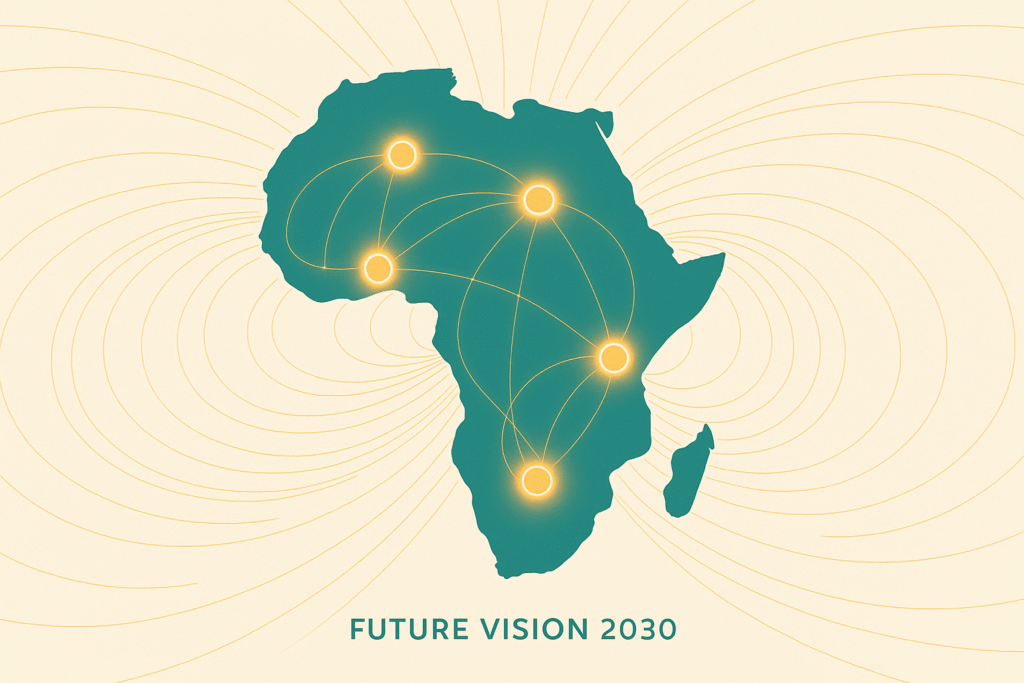

What success looks like by 2030

- A network of digital ports: Johannesburg, Lagos, Nairobi, Casablanca/Rabat, and Cairo, tied to live 2Africa/Equiano capacity and rich peering.

- Green-tilted power: solar and wind PPAs, plus storage, cutting diesel reliance—like the ADC/DPA solar build in South Africa and Teraco’s wind PPA strategy.

- AI-grade campuses: liquid-ready designs, high-density pods, and campus scale for GPUs.

- Sovereign-by-design workloads: payments, health, and public sector processed in-region (as Visa’s project signals).

- Startup effects: lower latency and predictable costs enable African teams to train and serve models locally, rather than relying on renting inference from a distant location.

Practical takeaways for builders and policymakers

- Choose metros like ports: Where interconnection is rich and multiple carriers land, your AI or cloud workload will be cheaper and faster.

- Request energy transparency: Demand published PUE and renewable energy share commitments, as they impact long-term costs.

- Design AI-first: If GPUs are even a medium-term requirement, pick facilities that already support high-density racks and liquid-cooling pathways.

- Compliance plan early: Payment, health, and public data rules are tightening. Local processing is becoming a competitive edge, not a headache.

- Build skills pipelines: Partner with universities and vendors on operations training; AI operations need electrical, mechanical, and software talent under one roof.

Conclusion: Hold the ports, shape the trade

Africa’s data centres are no longer back-office boxes. They are ports where digital trade docks—where subsea capacity meets cloud, where AI meets power, and where regulation meets reality.

The continent’s opportunity lies in rapidly growing capacity while hard-wiring renewables, standardising regulations, and designing for AI from the outset.

If Africa gets this right, the next decade won’t just be about consuming models built elsewhere; it will be about creating its own. It will be about originating them—training, tuning, and serving from African-run digital ports that anchor prosperity on the continent rather than exporting it over fibre.

Quick FAQ (for readers who skim)

- Why call them ports? Because they are the control points for digital trade—latency, interconnection, and regulation flow through them.

- Where’s the action? Johannesburg, Lagos, Nairobi—and a 500 MW plan in Morocco.

- What about sustainability? Solar and wind PPAs are on the rise; ADC’s 12 MW solar farm and Teraco’s wind PPA are significant moves.

- How do cables fit in? Equiano and 2Africa are the sea lanes; data centres are the harbours that turn bandwidth into value.