Google Project Suncatcher is Google Research’s proposal to scale AI compute in orbit using solar-powered satellites linked by free-space lasers. In this deep dive, we explain how the architecture works, why a dawn–dusk sun-synchronous orbit matters, what the economics look like, and which workloads might make sense for space-based AI.

The goal is to unlock near-continuous clean power, pack data-centre-class bandwidth between spacecraft, and one day make space a practical place to scale AI. This deep dive unpacks the architecture, economics, physics, risks, and what it could mean for AI over the next decade.

TL;DR

- Google proposes a constellation of small satellites in dawn–dusk sun-synchronous LEO, harvesting almost continuous sunlight and delivering ~8× more solar energy per year than mid-latitude ground panels. Google Research

- Satellites would carry Cloud TPU (Trillium/v6e) accelerators and use free-space optical inter-satellite links to reach multi-terabit bandwidth across the cluster; a lab demo already hit 800 Gbps each way (1.6 Tbps total) between a single transceiver pair.

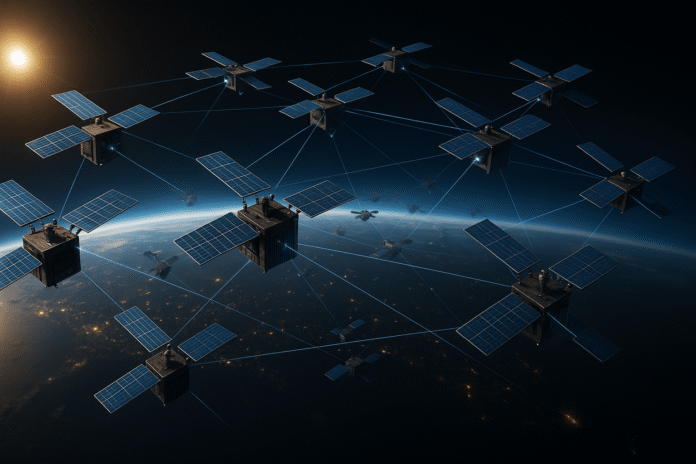

- Formation: an 81-satellite cluster within a ~1 km radius at ~650 km altitude, with 100–200 m nearest-neighbor spacing modeled as dynamically stable with modest station-keeping.

- Early radiation testing shows Trillium TPUs are more tolerant than you might expect; HBM is the most sensitive, but chips survived well beyond projected 5-year mission doses.

- The economic hinge: launch costs. If prices fall below ~$200/kg by the mid-2030s, Google’s analysis suggests launched-power costs could approach terrestrial data-center energy costs per kW-year.

- Next milestone: a learning mission with Planet—two prototype satellites by early 2027—to validate models, TPUs in orbit, and optical links. Google Research

What Google Project Suncatcher is actually proposing

On November 4, 2025, Google Research outlined Project Suncatcher, a space-based AI compute concept: a compact constellation of solar-powered satellites carrying Google TPUs, bound together with free-space optical (laser) links, operating in a dawn–dusk sun-synchronous orbit to maximise continuous solar power. The blog frames it as long-horizon research rather than a product announcement and links to a technical preprint.

The headline claim driving the orbital choice is energy productivity: in the right orbit, a solar panel can produce up to ~8× the annual energy of an Earth mid-latitude panel, while avoiding nights and seasonal dips—dramatically reducing or even eliminating the need for heavy battery storage.

Google’s team sketches a modular cluster rather than a single giant platform: think tens to hundreds of small satellites flying in tight formation, each with solar arrays, radiators, compute, and optical terminals. This spreads risk, lets you incrementally grow capacity, and, crucially, helps solve the networking problem at the heart of distributed ML. Google Research

The cluster architecture: how an orbital “data center” would cohere

Close-formation flying (the physics bit, made human)

To run modern ML at scale, accelerators must communicate at extreme rates. Google’s design studies model an 81-satellite cluster, with a radius of ~1 km, at ~650 km altitude, with 100–200 m spacing that oscillates predictably due to Earth’s gravity (the J2 effect from Earth’s oblateness is significant). Using Hill-Clohessy-Wiltshire dynamics plus a differentiable JAX-based refinement, the team shows such a cluster is stable with modest station-keeping.

Why that tight spacing matters: with free-space optical links, the received power falls off with distance squared; keep spacecraft hundreds of meters apart and you can push dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) and even spatial multiplexing to deliver tens of Tbps link capacity across the mesh—data-center-class bandwidth, in orbit. In lab, a single transceiver pair already demonstrated 800 Gbps each way.

Thermal realities for Google Project Suncatcher

Vacuum is both friend and foe: there’s no air to convect heat, so you must conduct heat out to radiators. Google calls for advanced thermal interfaces and think heat pipes or loop heat exchangers feeding large, view-factor-optimised radiators. The thermal issue is not yet resolved; it’s flagged as a top item for future milestones.

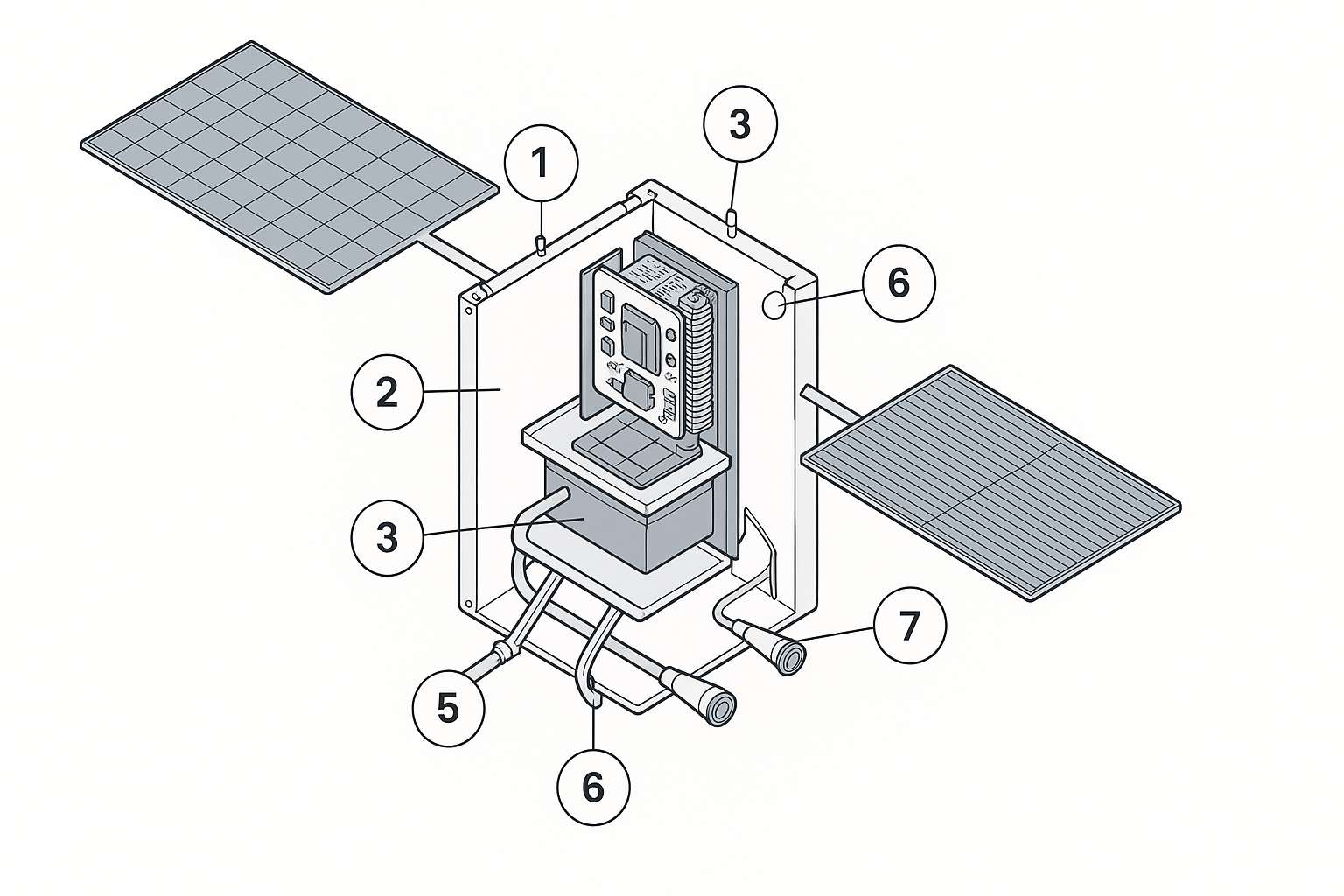

- Deployable solar arrays

- Power conditioning / DC-DC stage

- Compute module (TPU + HBM card)

- Thermal interface & copper spreader

- Heat pipes to radiator

- High-emissivity radiator fins

- Free-space optical terminals (laser links)

Compute and memory in radiation

The team irradiated Trillium (v6e) Cloud TPU silicon with a 67 MeV proton beam to emulate LEO space dose. HBM (high-bandwidth memory) showed the most incredible sensitivity (uncorrectable ECC events do occur). Still, no hard TID failures up to 15 krad(Si) on a tested chip, and per-event error rates look acceptable for inference.

Training under SEE (single-event effects) needs further study, but the headline is: commercial TPU silicon may already be ” radiation-hard enough” for specific space ML tasks.

Ground connectivity is its own R&D program

Inter-satellite bandwidth is only half the equation; you still have to ingest data and deliver results to Earth. The paper points to laser ground links as an active area, citing NASA’s TBIRD demo at ~200 Gbps as a data point. Pushing multi-hundreds of Gbps through the atmosphere, while tracking fast-moving targets with precision beam pointing and handling turbulence, remains an open, solvable challenge.

Why space at all ? Power density, duty cycle, and land/water reliability

Suncatcher’s core thesis is energy and scale. The Sun delivers continuous, high-duty-cycle power in SSO, avoiding the deep intermittency that dogs terrestrial solar and reducing planetary impact on land, water, and grid siting.

Panels in certain orbits can net up to ~8× annual production vs. a comparable mid-latitude ground array, which is a massive lever on $/kW-year and on embodied infrastructure like batteries and substations.

The design also minimises terrestrial resource contention : you’re not competing for grid interconnects, cooling water, or hyperscale-sized parcels. And the power-to-mass optimisation can go further than Earth designs—if launch costs cooperate.

The economics of Google Project Suncatcher

Google’s modelling compares “launched power price” (amortised $/kW-year to get solar + compute to LEO and operate it) with US terrestrial data-centre energy spend, quoted as ~$570–$3,000/kW-year depending on grid prices and PUE.

Under a plausible learning curve, especially with Starship-class reuse LEO launch below ~$200/kg by mid-2030s, moves launched power into the same ballpark as Earth power on a per-kW-year basis. If launch stalls closer to $300/kg, it’s still within strategic reach for specific workloads.

The paper’s historical back cast shows SpaceX’s trajectory from >$30,000/kg (Falcon 1) down to ~$1,800/kg (Falcon Heavy) over ~100 flights.

It explore reuse scenarios suggesting <$250/kg customer pricing if 10× component reuse is sustained (and potentially ~$60/kg for LEO under extreme assumptions). These are not guarantees, but the direction of space travel is key for feasibility.

What workloads make sense in orbit?

Short answer: not everything, at least at first.

- Batch inference on large models: High duty cycle and predictable inputs make sense where latency isn’t user-visible (e.g., nightly personalization refreshes, content moderation queues, large-scale embeddings, model-assisted science pipelines).

- Training: The SEE sensitivity of HBM and the difficulty of fault-containment during long runs are open questions ; the team flags further work before training looks routine in LEO. Redundant provisioning and error-aware schedulers will be mandatory.

- Edge-adjacent compute (earth observation, astronomy, climate): Proximity to sensors (e.g., imaging constellations) plus on-orbit pre-processing could relieve downlink bottlenecks by shipping distilled outputs to ground. Google’s first learning mission with Planet is a hint in that direction. Google Research

On the other hand, anything that must respond in tens of milliseconds to end users—think conversational assistants or in-the-loop control—will prefer ground for a while, because even LEO adds path latency and the ground laser link budgets won’t be everywhere, all the time, for years to come.

The big technical choke points (and how Suncatcher addresses them)

- Bandwidth between accelerators

Modern ML scales by cranking all-reduce and shuffles across accelerators. Suncatcher attacks this with short-range laser links, DWDM channel stacking, and spatial multiplexing, enabled by hundreds-of-meters proximity. Early lab results (1.6 Tbps per transceiver pair) are promising; the target regime is tens of Tbps per link in the cluster mesh. - Close formation flight

Flying 100–200 m apart at 7.5 km/s is non-trivial. The models here incorporate Earth’s J2 term and show bounded relative motion over an orbit—picture a rotating ellipse of relative positions—and modest station-keeping to hold shape. This is new territory compared to kilometer-spaced comm constellations. - Radiation + reliability

The test data imply TPU logic is resilient to TID ; HBM sees uncorrectable ECC, but at rates potentially tolerable for inference. System-level mitigations (checkpointing, job slicing, error-aware placement) and redundant capacity will be the safety net while the hardware and firmware coevolve for space. - Thermal

With no air, everything rides on conduction and radiation. Google flags thermal interface materials and passive heat transport as research areas ; expect radiator geometry optimisation, high-emissivity coatings, and compute–radiator co-design to be major levers. - Ground links

Laser comms to Earth is improving (see TBIRD ~200 Gbps) but scaling to multi-hundreds of Gbps persistently across weather, daylight, and regulatory constraints is a system-of-systems challenge (sites, networks, buffering). It’s solvable, not solved.

Roadmap and who else is moving

Google positions Suncatcher as research with milestones, not a product launch. The 2027 learning mission with Planet (two satellites) is the proof-point: validating orbital dynamics, optical links, and TPU behaviour in the real space environment. Independent industry reporting echoes the 81-satellite cluster concept and timeline.

Beyond Google, a wave of companies is exploring space data centres from startup concepts to national programs. Coverage notes StarStarcloud’s Nvidia-backed path and other entrants imagining monolithic “data centre in space” builds. Google’s choice to go modular-constellation highlights a different trade-space: more networking complexity in exchange for incremental scale and lower assembly risk.

Environmental and policy angles

Proponents pitch Suncatcher as an energy scale without land/water strain; critics point to launch emissions and upper-atmosphere impacts. A European analysis cited by Semafor suggests space data centres become environmentally favourable only if reusable launch keeps emissions <~370 kgCO₂/kg payload over lifecycle—something future heavy-reuse vehicles may approach, but not proven today. The climate calculus will track propulsion chemistry, reuse cadence, and total payload mass over time.

There’s also orbital debris and space traffic management. Tight formations add new safety practice needs: autonomous collision avoidance, secure station-keeping, and responsible deorbit plans. None of this is insurmountable, but it pushes regulatory frameworks (FCC/ITU/NOAA equivalents worldwide) into fresh territory.

What it could mean for industry—and for regions battling power constraints

If the economics close, Suncatcher-style constellations could become “overflow capacity” for power-hungry, latency-tolerant AI jobs, softening pressure on terrestrial grids in regions with tight capacity or water stress. For the Global South, especially places facing data-center moratoriums due to power and water scarcity, orbit-hosted cycles could be an imported compute option—assuming downlink hubs and data-sovereignty policy rails are put in place.

For Earth-bound operators, space compute won’t replace hyperscale campuses; it slots alongside nuclear, geothermal, and grid-tied renewables portfolios as a high-capex, potentially low-OPEX adjunct. And it’s a forcing function: drive optical networking, radiation-tolerant memory, and thermal metamaterials forward, and those wins will echo back into ground data centres.

What to watch next for Google Project Suncatcher

- 2027 Planet learning mission : Did the optical link work at meaningful rates ? Did TPUs meet predicted error budgets ?

- Launch price curve: Are credible providers—Starship-class and competitors—delivering <$300/kg by early 2030s and marching toward $200/kg targets?

- HBM hardening & firmware: Do we see ECC strategies and architectural changes reducing SEE-induced job impact for training in particular?

- Thermal demos : Any breakthroughs in passive radiators or integrated compute–radiator–array prototypes?

- Ground laser networks : TBIRD-style demos stepping from 200 Gbps to multi-hundreds with operational availability across sites.

The take: moonshot with a plausible path

Google isn’t claiming “data centers in space by 2028.” They’re stating something more interesting: no law of physics forbids space-based ML clusters, and given launch learning curves and commodity optical tech, we might cross an economic threshold in the 2030s.

The hard problems are eminently engineering—thermal, memory robustness, formation control, and building a ground laser network at scale.

If launch learning curves, optical networking, and radiation-tolerant memory converge, Google Project Suncatcher becomes a credible new plane of AI capacity one kilometre wide, 650 kilometres up.