The AI boom isn’t only about more innovative models. It’s about who controls the pipes, the power, and the people behind them. That’s the real battle for Africa’s AI future—and the decisions made this decade will lock in winners and losers for a generation.

Across the continent, three levers determine power: compute, data, and talent. Own them, and you shape outcomes. Rent them, and you pay a premium to use intelligence that has been trained elsewhere.

The African Union’s new continental AI strategy puts this bluntly: policy must turn ambition into interoperable rules and investment.

The framework was formally adopted in July 2024, setting a roadmap for 2025–2030.

Why Ownership Matters

Ownership changes incentives. If compute sits offshore, high-value work sits offshore. When data leaves the continent, value is extracted twice—first as raw data, then as finished intelligence sold back to the source. If the best engineers leave, their capabilities decay at home.

Consider three simple questions that determine bargaining power:

- Where do models train and run?

- Who governs the data pipelines that feed them?

- Where do the next 100,000 applied AI practitioners build their careers?

Compute: From Renting to Building

Africa’s AI ambitions rise and fall on the hardware beneath them. Compute is more than just servers; it’s the foundation that determines whether local innovators can train, deploy, and own their models. From global hyperscale clouds to sovereign GPU clusters, the continent is shifting from renting power abroad to building it at home.

Hyperscale regions are finally on the map.

Cloud regions within Africa reduce latency and support data residency needs. Amazon opened AWS Africa (Cape Town) in 2020. Google Cloud Johannesburg went live in January 2024. Microsoft Azure lists South Africa (North) and South Africa (West) among its official regions. Together, these reduce round-trips and enable regulated workloads to stay on the continent.

There’s more coming. Microsoft and UAE-based G42 have announced a $1 billion investment in a Kenya data centre complex that will power a new Azure region for East Africa, utilising geothermal energy. This isn’t just capacity; it’s a template for region-specific cloud backed by local power.

For more on infrastructure rollout across Africa, see AI Adoption in Africa: Opportunities, Challenges & Roadmap.

Sovereign compute: the Cassava–NVIDIA gambit.

The most ambitious move is Cassava Technologies partnering with NVIDIA to deploy “AI Factory” infrastructure across South Africa first, then Egypt, Kenya, Morocco, and Nigeria. Bloomberg reported the deal as the continent’s first AI factory, with NVIDIA tapped to provide accelerated computing and software.

Cassava says the first clusters stood up in South Africa in 2025, with expansion planned across their pan-African network. Several trade outlets and Cassava releases estimate the program’s cost at around $700 million. The through-line is simple: keep training-grade compute and sensitive data within Africa.

Whether this becomes a continental asset or a single-vendor island will depend on access terms for startups, researchers, and public institutions. However, the signal is clear: sovereign GPU capacity is shifting from software to construction sites. That matters for Africa’s future with AI.

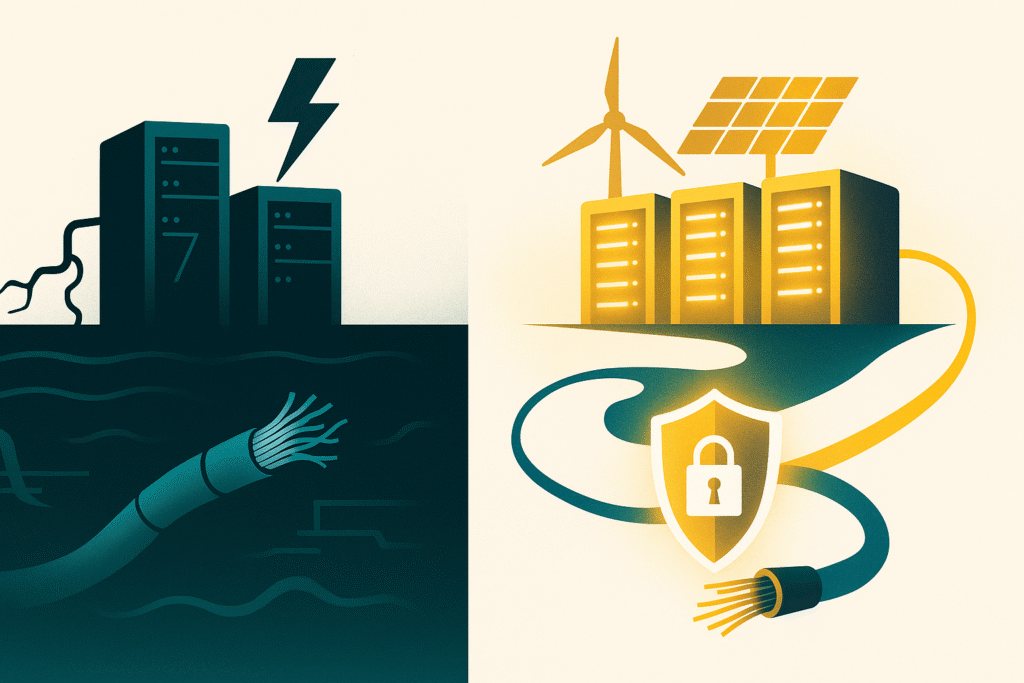

Bandwidth is destiny

Computing without bandwidth is a paper tiger. Two cables define the next leap:

- 2Africa, a nearly 45,000 km system encircling the continent, will connect dozens of landing points and is slated to be fully operational by the mid-2020s. It’s designed to boost resilience and lower transit costs at scale.

- Equiano (Google) links Portugal to South Africa, with branches in Nigeria, Togo, Namibia, St. Helena, and more, bringing significant capacity upgrades along the Atlantic coast.

Outages show why redundancy matters. In March 2024, multiple cables in West and Central Africa failed, causing widespread disruption. In September 2025, several Red Sea cables were cut, forcing Microsoft to reroute Azure traffic and warning of higher latency.

These events demonstrate that subsea routes are crucial infrastructure for AI workloads, not just for video streaming.

Data centres are scaling—and spreading inland.

South Africa is the anchor. Teraco’s JB4 campus near Johannesburg completed a new 30 MW phase in August 2025, bringing the site’s total capacity to 50 MW of critical IT load and enabling high-density, liquid-cooled AI deployments. It’s now billed as Africa’s largest standalone data centre.

Nigeria is diversifying beyond Lagos. Equinix (which acquired MainOne) announced PR1 Port Harcourt, the first cable landing station in Nigeria outside Lagos and a site for the 2Africa system—part of a broader $140 million expansion across Southern Nigeria. This helps de-risk concentration and push capacity closer to users and the industry.

South Africa’s overall data centre market reflects the trend. Industry trackers estimate $2.16 billion (2024) → $3.40 billion (2030). Capacity is growing because workloads are shifting to the home. That’s good for latency, compliance, and cost control.

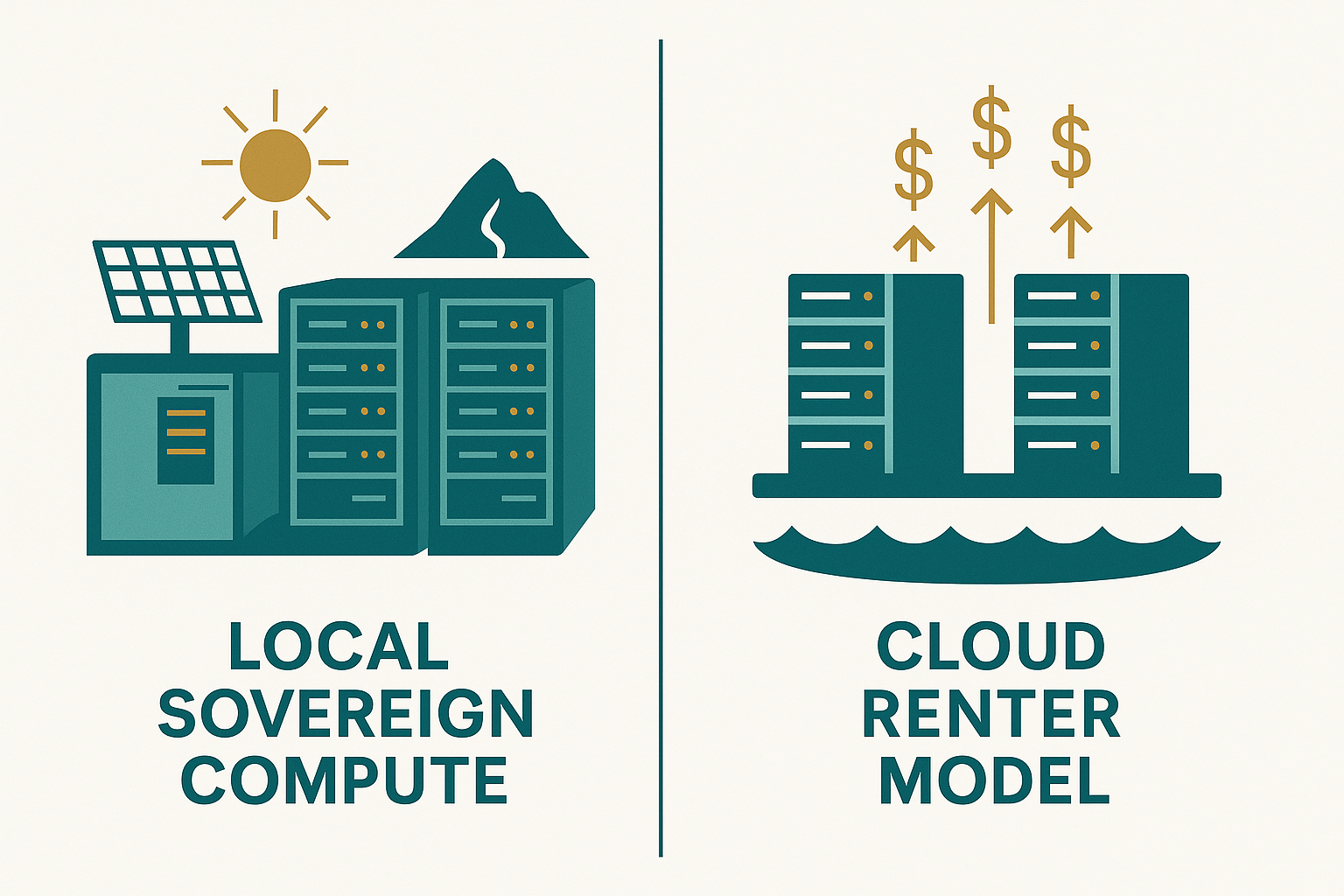

Bottom line: If compute is rented forever, margins and leverage live elsewhere. Local regions, sovereign GPU clusters, and inland landing stations improve the balance sheet for Africa’s AI future.

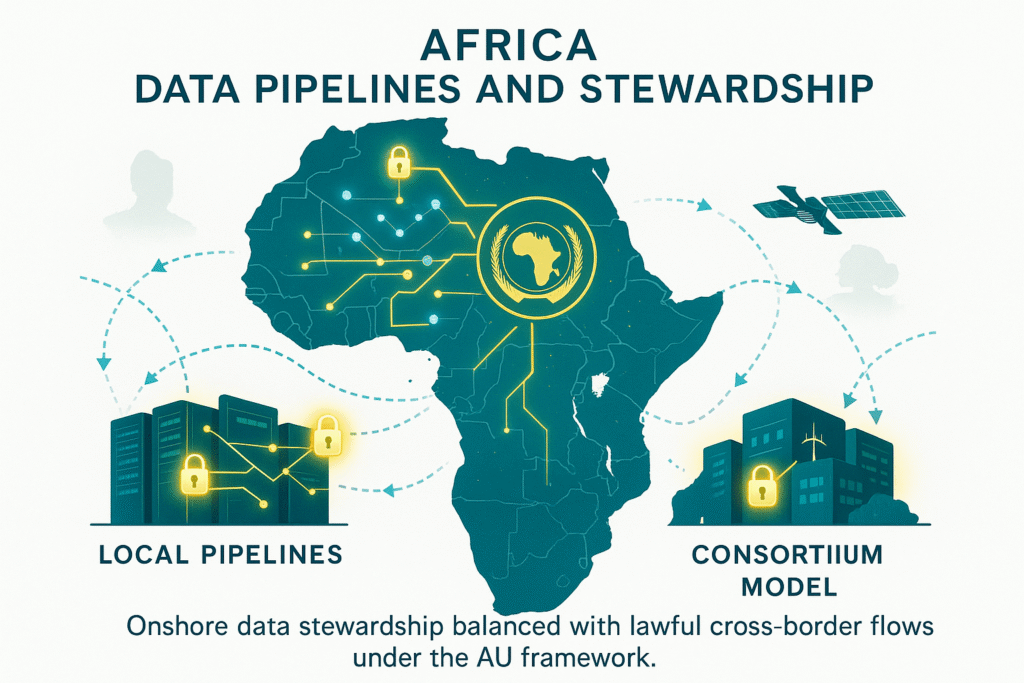

Data: Law, Localisation—and Smart Flow

If compute is the engine, then data is the fuel—and whoever governs its flow governs the value chain. Africa’s choices on data localisation and stewardship will decide whether value is extracted offshore or recycled back into local economies. The challenge is to balance protection with openness, and the African Union has begun sketching that blueprint.

The continental frame

The African Union’s Continental AI Strategy outlines a path to harmonise governance, promote responsible innovation, and reduce regulatory fragmentation across 55 jurisdictions.

The plan sets an implementation window through 2030, with a preparatory phase in 2024. That matters to investors who need clarity on cross-border rules.

National enforcement is getting real.

- Nigeria: The Nigeria Data Protection Act (2023) established the NDPC, which has the power to enforce privacy rules. In 2024, Reuters reported the commission’s largest fine to date against a bank for violations, underscoring a new appetite to act.

- Kenya: The ODPC has issued enforcement and penalty guidance and levied fines under the 2019 DPA and its 2021 regulations. Companies now plan governance with Kenya’s regulator in mind.

- South Africa: POPIA restricts cross-border data transfers unless adequate protection is in place or explicit conditions are met. Firms may require regulatory authorisation for sensitive categories, with fines of up to ZAR 10 million or a share of their turnover.

This isn’t “data isolationism.” It’s a move toward data stewardship: keep high-risk datasets onshore under audited access, enable federated learning and lawful transfers for the rest, and avoid a patchwork that throttles innovation. That model aligns with the AU strategy and the reality of global cloud.

The practical tension

Sovereign data rules must coexist with resilient networks. When subsea cables fail, the internet reroutes through alternative paths—sometimes across regions with different legal regimes. The March 2024 and September 2025 outages highlighted this risk. Resilience plans should include legal “playbooks” for cross-border routing during incidents, not just technical failover. Reuters+1

Takeaway: Sensible residency rules + harmonised transfers = more investment and safer AI pipelines. That shapes Africa’s AI future more than any single model release.

Talent: The Compounding Advantage

Even with compute and data in place, nothing happens without skilled people. Talent is Africa’s most renewable resource, and unlike servers or cables, it compounds over time. The question is whether Africa’s next generation of AI engineers will build careers locally—or export their skills abroad.

The numbers and the momentum

Google and Accenture’s Africa Developer Ecosystem 2021 estimated 716,000 professional developers across the continent—a base that has continued to grow as AI skills become more widespread. It’s an old number, but it shows a significant starting point for capacity building.

On the open-source side, GitHub’s Octoverse 2024 reported a nearly 59% surge in contributions to generative AI projects and an almost 98% increase in project counts year-over-year, driven by a global community that is increasingly inclusive of Africa. That energy spills into local labs and startups.

This echoes findings in Will AI Replace African Jobs? Here’s the Real Answer, which shows how skills demand is shifting.

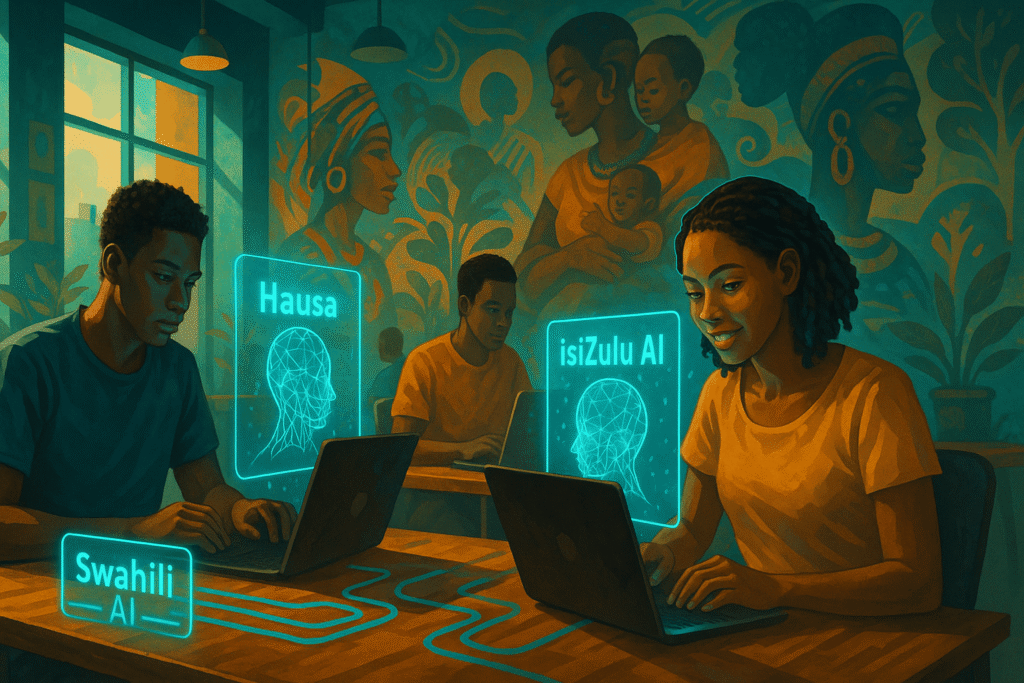

Local language AI is a strategic wedge.

Grassroots research communities, such as Masakhane, are building datasets and benchmarks for African languages, addressing the bottleneck of scarce, clean data for NLP. Startups such as Lelapa AI launched models and services (InkubaLM, Vulavula) focused on African languages, with reported training datasets in the billions of tokens. This is how you localise AI beyond English and French.

Policy complements pipelines

Countries are competing to attract researchers and startups, not just data centres. Rwanda’s C4IR centres focus on policy work related to data governance and AI; Egypt has published the second edition of its National AI Strategy for 2025–2030, aiming to scale skills, infrastructure, and responsible use. These moves matter because they combine visas, grants, and public-sector demand.

Net effect: Talent compounds. If trained professionals can access computing resources and datasets at home, projects stay local—and Africa’s AI future tilts toward origin, not import.

Three Ownership Models (and Their Trade-offs)

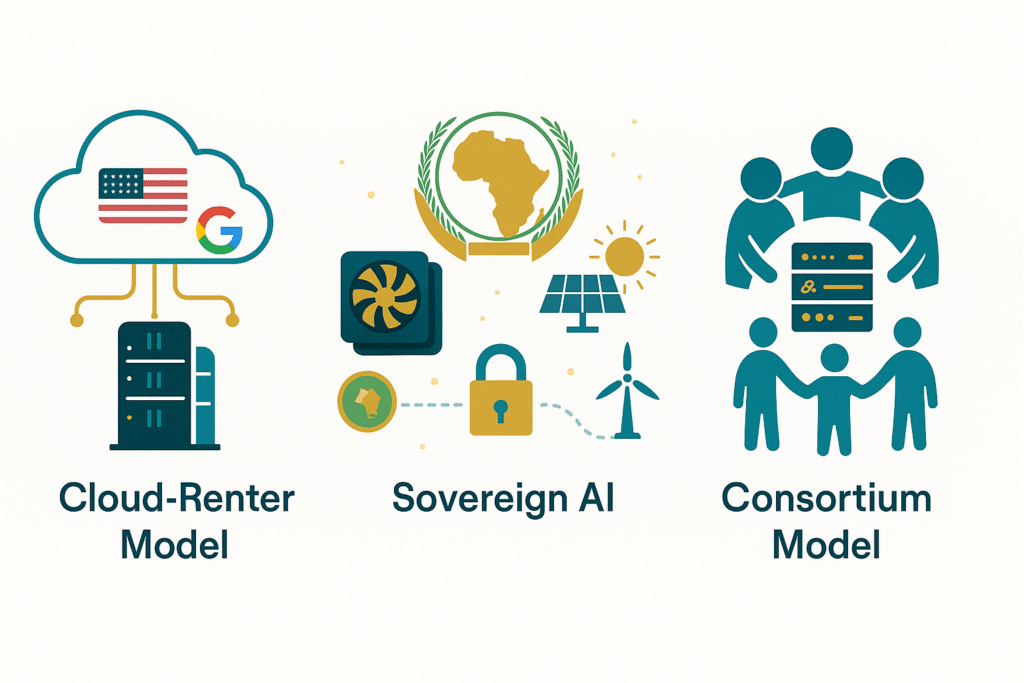

1) Cloud-renter model

Fastest way to ship. Build on AWS, Azure, or Google; pay per token and scale on demand. This suits lean startups and pilots, but it leaks margins and negotiating power to external providers. The risk: strategic workloads and sensitive data may never live locally.

2) Sovereign AI model

National or regional GPU clusters with clear access rules for universities, startups, and critical public agencies. It’s capital-expenditure (CapEx)-heavy and execution-intensive, but it builds long-term advantage if coupled with reliable power sources (such as renewables) and strong procurement. The Cassava–NVIDIA rollout is the bellwether here.

3) Consortium model

Telcos, IXPs, data centre operators, and universities form pan-African cooperatives to co-own compute resources, land cable landings outside the usual hubs, and host open models. Governance is more complex, resilience is better, and bargaining power rises with scale—see Equinix’s PR1 in Port Harcourt as an example of spreading landing risk beyond a single metro.

Many small businesses still lean on off-the-shelf tools — see Top 10 AI Tools for Small Businesses 2025 for examples of what’s being used today.

Case Study Signals to Watch (2025–2027)

- Cables & landings: 2Africa branches lighting up outside the classic hubs; PR1 Port Harcourt as Nigeria’s first non-Lagos landing; impact on transit pricing and latency.

- Data-centre density: Teraco’s high-density AI halls (5 MW per hall) and liquid cooling; how quickly tenants fill JB4/JB5.

- New regions: Progress on the Microsoft–G42 Kenya cloud region; timelines from LOI to go-live.

- Sovereign GPU access: Actual AI-as-a-Service pricing and research credits from Cassava–NVIDIA; university and startup uptake.

- Policy teeth: NDPC enforcement patterns in Nigeria; ODPC rulings in Kenya; POPIA cross-border guidance in South Africa.

- Language models: Output from Masakhane, Lelapa and allied labs; evidence of African-language models in production support, public services and commerce.

Practical Playbook: What “Ownership” Looks Like

1) Anchor compute locally—then tie it to access.

Back hyperscale and sovereign clusters with renewable PPAs and reliable cooling. Reserve research quotas, offer credits to accredited startups and universities, and publish transparent price sheets. (Teraco’s new AI-ready halls show the hardware direction.)

2) Codify data stewardship, not isolation.

Keep high-risk datasets (such as health, ID, and education) onshore with strict audit trails in place. Enable federated learning and standardised contractual clauses for cross-border transfers. Align national rules with the AU framework to cut compliance friction.

3) Fund public-good datasets.

Commission labelled corpora for Swahili, Hausa, Yoruba, isiZulu, Amharic and niche domains (law, health, agri-extension). Put them under clear licenses and ethics protocols; partner with Masakhane and universities to curate.

4) Turn telcos and IXPs into AI landlords.

Incentivise them to co-own inference hosting, model hubs, and on-net caches at neutral facilities located in Lagos, Nairobi, Johannesburg, and Cairo. PR1’s non-Lagos landing is the posture to copy.

5) Build talent flywheels.

Scale vendor-agnostic curricula and attach grant funding to measurable outcomes (open models, tools, and startups). Support national labs tied to public-sector demand. Track the pipeline using Octoverse-style metrics for AI repos and contributors.

Comparisons: Originator vs Consumer Economies

Originator economies train and serve models domestically; they license weights, export AI services, and retain sensitive data locally. Their universities publish state-of-the-art work because they can access GPUs without having to beg. Their telcos earn from AI hosting, not only transit.

Consumer economies ship raw data out, repurchase AI through APIs, and struggle to justify high-value AI research and development budgets. Their best engineers become remote implementers, not platform builders. The cost gap compounds over time. That is the stark choice for Africa’s future with AI.

Risks to Manage Now

The infrastructure race isn’t only about opportunity—it’s also about vulnerabilities. Outages, power shortages, and lock-in can undo years of progress if not managed early. Africa’s AI strategy must therefore include resilience alongside growth.

- Vendor lock-in: One sovereign cluster is not a sovereign cluster. Build multi-vendor procurement and enforce open standards.

- Power constraints: AI loads are power-hungry. Tie new DCs to wind, solar, hydro, and geothermal (Kenya’s geothermal-powered region is instructive).

- Security & Resilience: Protect landing stations and inland fibre networks. The 2024 West/Central Africa and 2025 Red Sea incidents should trigger cable-security playbooks and diversified paths.

- Data misuse: Strong DPIAs (data protection impact assessments) and red-team audits for high-risk AI (health, finance, identity). Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa already have enforcement levers—use them.

What Success Looks Like in 24 Months

Success won’t be abstract; it will be measurable. By 2027, progress can be tracked in GPU clusters, cable landings, and the number of African-language models in production. These milestones will signal whether the continent is on the path to becoming an originator economy.

By late 2027, success is visible if:

- Two or more sovereign GPU clusters are live with public research access and startup credits.

- 2Africa landings outside traditional hubs are active and carrying traffic.

- At least one East-African cloud region is serving regulated workloads on geothermal power.

- Multiple African-language models are being utilised in production for customer support, health triage, or agricultural advice.

- Coherent data-transfer guidance exists across AU members, reducing contract friction for cross-border training and inference.

Hit those, and Africa’s AI future tilts toward originator status—exporting not only culture and commodities, but intelligence.

Conclusion: Choose the Asset Register, Not the Slogan

This isn’t about rhetoric. It’s about an asset register with dates and megawatts, including cable landings, DC megawatts, GPU counts, public datasets, and the payroll of personnel authorised to use them. The nations and consortia that own compute, data, and talent will write the terms of Africa’s AI future. Everyone else will keep renting it—expensively.

The next decade won’t wait. Build muscle, govern data, grow minds.